Affirmative action in Medicine : A forbidden debate?

What the reaction to an affirmative action paper tells us about the institution of Medicine in America today

As a young boy, I grew up reading of the triumph of good over evil in my favorite Indian comic book: Amar Chitra Katha. The tales of the virtuous vassals imbued by a godly spirit vanquishing the forces of darkness is powerful and appealing in large measure because we believe we inhabit a world where the good guys won. But unlike the comic books, the bad guys in the real world don’t have horns, and don’t look like J.R.R Tolkien’s trolls - they wear suits and have fancy degrees and appear quite respectable. Would it be really obvious if the bad guys won? History is after all replete with examples of revolutionaries who believe themselves to be virtuous, blindly following a degenerate elite into an amoral abyss.

With this in mind, a lawsuit from the world of American medicine, filed by Dr. Norman Wang against his employer and others is particularly enlightening.

This particular affair began when Dr. Wang published a paper in the Journal of the American Heart Association titled “Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity: Evolution of Race and Ethnicity Considerations for the Cardiology Workforce in the United States of America From 1969 to 2019 “. The purpose of this white paper was to “provide an overview of policies that have been created to impact the racial and ethnic composition of the cardiology workforce, to consider the evolution of racial and ethnic preferences in legal and medical spheres, to critically assess current paradigms, and to consider potential solutions to anticipated challenges.”

At the time of the publication in March 2020, Norman Wang was a cardiologist, a member of the faculty of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and director of the fellowship program in clinical cardiac electrophysiology at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC). His publications to this point had largely consisted of esoteric matters in the field of his expertise : electrophysiology. This publication, was of an entirely different nature. The article asserted that the medical profession had not been successful in its overarching goal of increasing the percentages of underrepresented races and ethnicities in the medical profession, and particularly in cardiology. The article also noted that programs to achieve these diversity goals applied different standards to applications by members of underrepresented races and ethnicities and thus raised questions about the legality of doing so because of how race was being used as a factor in hiring, recruitment, promotion and admissions.

The article went through the usual academic peer review process and was published online on March 24, 2020., concluding with the following passage that quoted affirmative action proponent Faith Fitzgerald,

As Fitzgerald envisioned, “We will have succeeded when we no longer think we require black doctors for black patients, chicano doctors for chicano patients, or gay doctors for gay patients, but rather good doctors for all patients”. Evolution to strategies that are neutral to race and ethnicity is essential. Ultimately, all who aspire to a profession in medicine and cardiology must be assessed as individuals on the basis of their personal merits, not their racial and ethnic identities.

All was quiet for months, perhaps in part because our fearless medical leaders were busy supporting policies that trampled over the civil liberties of ordinary citizens to stop COVID (Spoiler alert: everyone got COVID anyway).

But per the lawsuit, in late July 2020, certain faculty physicians, executives and colleagues learned of the article and objected to the conclusions of the article because they were problematic and embarrassing. In a meeting that took place July 31, 2020, Samir Saba, the chief of the division of cardiology at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPSOM), and Kathryn Berlacher, associate chief of education in the division of cardiology and program director for the cardiology fellowship program at UPSOM met to discuss the matter with Dr. Wang. During the course of the conversation, Dr. Wang told Saba and Berlacher that the selection process for the medical education program at UPSOM and the graduate medical education program at UPMC were violating federal law because of the racial and ethnic preferences they employed. Shortly after this meeting, Dr. Wang was removed from his roles as the director of the fellowship program in clinical electrophysiology. Additionally, Saba and Berlacher, forbade Dr. Wang from having any contact with individuals in any fellowship programs at UPMC, residents or medical students at UPSOM.

Around the same time Dr. Wang was being punished at work, an organized social media campaign that eventually included Dr. Wang’s colleagues began in earnest. One of the first tweets came August 2nd, from a medical student aghast that a leading cardiology journal would publish an opinion arguing against affirmative action.

The viral thread made mince meat of the carefully chosen words in the article : “there exists no empirical evidence by accepted standards of causal inference to support the mantra that “diversity saves lives” and didn’t include the paragraph that came immediately prior discussing the existing research on diversity and mortality. In the course of disagreement on any number of topics Wang’s treatment of the issue was pretty standard. He didn’t say there was no evidence that diversity saved lives, his argument was that the data underpinning this was flawed.

It is understandable for activist medical students to be less than familiar with the usual back and forth of scientific arguments, but actual practicing cardiologists confirmed the growing consensus that Wang had arrived at an unacceptable conclusion.

Berlacher, the Pitt cardiology fellowship director who had days before met with Wang about the article, joined the social media pile-on later in the day, and called the article “scientifically invalid and racist”.

The following day, Barry London, the editor of the Journal of the American Heart Association penned a response apologizing for publishing the article, and a few days later the article was retracted.

According to London, while the paper may have claimed to be a white-paper about diversity initiatives, “its central purpose was to argue against affirmative action, noting that Black and Hispanic trainees in medicine are less qualified than White and Asian trainees. “ London went onto affirm that “these opinions do not reflect in any way my views, the views of the JAHA Editorial Board, or the views of the American Heart Association. We condemn discrimination and racism in all forms.”

An opposing viewpoint was finally published in June 2021 in the same journal by Karim et. al. to respond to Wang with “data and facts”. Because it was hard to find anyone engaging with the actual content of Wang’s article in the social media firestorm, I was very interested in reading the rebuttal.

The authors spend the first part of the article restating the fact of the poorer health status of black patients in America before attacking Wang for not providing the appropriate context for his claims. They don’t clearly find anything wrong with any particular claim of Wang’s, their thesis is that Wang’s contentions without appropriate context results in the wrong conclusion. This is a perfectly reasonable claim, but recall the article was retracted - a fate reserved for fraud and gross factual errors. Papers aren’t usually retracted because they arrive at the wrong conclusion because they lack context.

Some examples from the rebuttal follow.

Wang noted in his paper the student doctor network has an online calculator that suggests the three most important factors in admission to medical school are MCAT score, grade point average, and race. An accompanying figure in the article that shows a wide variance in acceptance rates to medical school by race is used in the article to support that contention. More than 50% of African-American applicants with MCAT scores <23 were accepted to medical school, while only 10% of Whites and Asians with the same scores were accepted.

Authors of the rebuttal state:

This is a simplistic view that completely dismisses applicants' research, volunteering efforts, unique backgrounds that could enrich the medical community, and quality of the personal statements that all schools require. Usually, the selection and interview process for any stage in medicine is much more complex than rationalizing it based solely on scores.

Nothing in that statement rebuts Wang’s claim that race may be a fundamental factor in medical school admissions, so much so that a popular on-line calculator uses your self identified race as one of three factors when determining the chances of acceptance to medical school.

Another example.

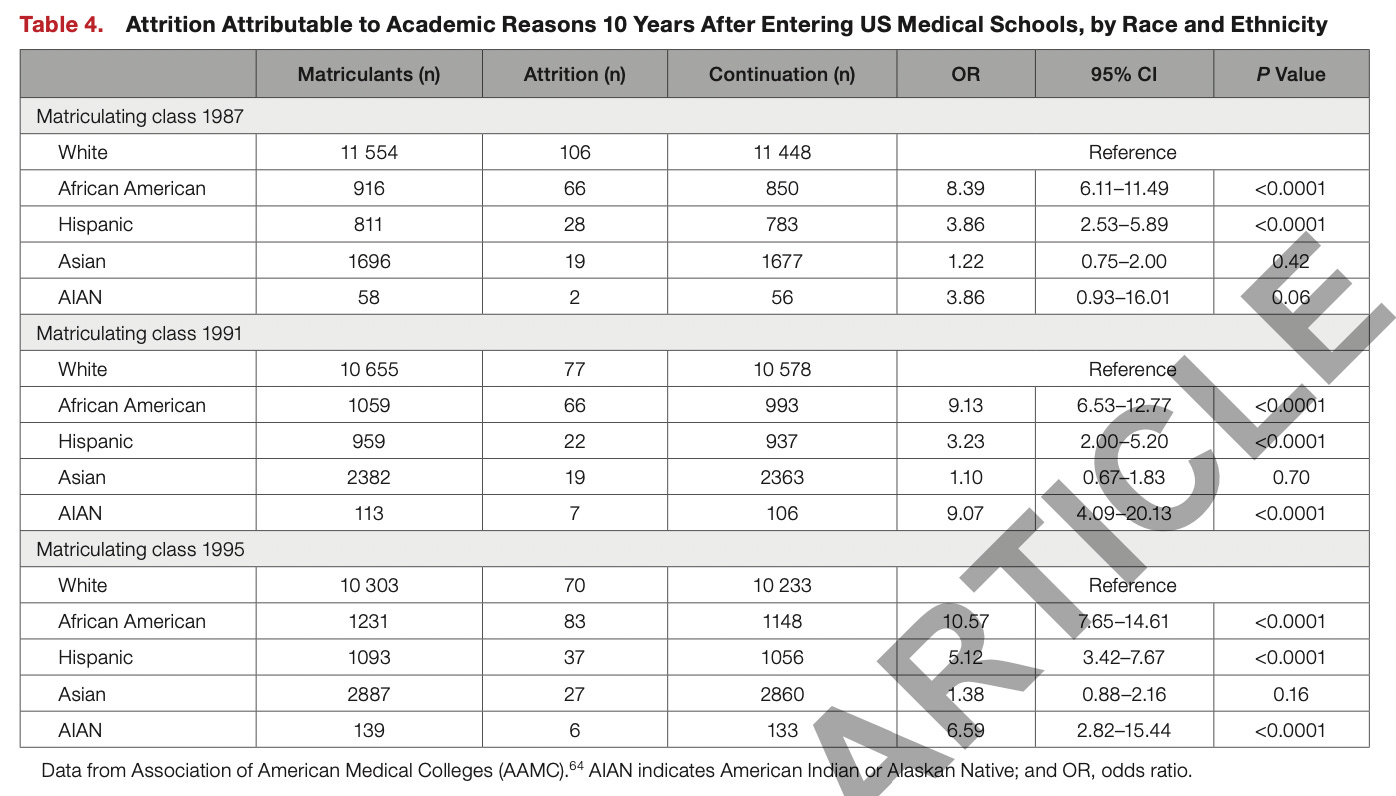

Wang displays a chart that shows wide disparities in academic attrition rates by race. In the matriculating medical school class of 1987, African American medical students were 8 times more likely than White medical students to not graduate. In 1995, African American medical students were 10 times more likely to not graduate than White medical students.

The rebuttal :

The attrition rates mentioned in Table 4 use White race as reference, which gives you the entire sense of what is normative to the author. Unfortunately, the sentiment of being "White adjacent" and "model minority" is often prevalent in Asian immigrant cultures and adds to the already strained race relationships in this nation.

If you’re confused about how that’s a rebuttal and what being a model minority has to do with data that seems to show higher medical school attrition rates by race, you would not be alone. You could use Hispanics as the reference, or African Americans and the data would still tell you the same thing.

A third example:

Wang attempts to question one of the central planks of affirmative action - that more URM physicians lead to greater access for underserved populations - by pointing out data showing URMs serving minorities were less likely to be board certified, and may be choosing primary care in underserved areas because they were less qualified. Importantly, these are not Wang’s opinions - he is using a reference for the fact board certification rates are indeed lower, and quoting a 1994 paper published in the Journal of the National Medical Association about the poorer qualifications of those serving in underserved areas.

If this is all about the patients, and we are actually concerned about the genesis of poorer health outcomes for URMs, being careful not to create a system that could lead to poorer care seems a reasonable concern.

The rebuttal :

Board certification is a metric that is based on financial application for taking standardized tests. Economic endeavors that are necessary to succeed in medicine include thousands of dollars in MCAT preparatory classes (for those who can afford it), fees for the MCAT, application fees for medical school, traveling for interviews to get into medical school, followed by low wages during years of training with expectation to pay a large sum for US Medical Licensing Examinations, further postgraduate applications, and traveling for interviews for positions. What is also not mentioned is that hundreds of thousands of dollars in medical school tuition is compounded, which can further hinder those without an affluent background. Applicants from underserved communities may not have the economic resources to continue this process.

The author speculates that working in underserved areas results from an inability to procure jobs in desirable locations because of lower qualifications. There are many physicians providing care for large sections of society where medicine is otherwise failing to intervene. In fact, access to care as well as quality and intensity of care contribute to lower quality as well as quantity of life for racial/ethnic minorities. Although there are references on Black patients getting managed less frequently by board‐certified physicians and receiving less high‐quality service, there is no mention of alternative solutions to serve their needs

Again, I see no counter to Wang’s claim. The counter simply appears to be that care is being delivered to URM’s and that’s what’s important. And it sure sounds like the Journal of the American Heart Association published a viewpoint critical of board certification as an indicator of quality because it has more to do with the ability to pay for the process. Given the implication that URM physicians are less frequently board certified because they lack financial privilege, it would seem the authors are suggesting board certification could be systemically racist. Yet, the same authors very upset with Dr. Wang about presenting problems without providing solutions, do not call for an end to board certification.

A final example:

A particularly interesting part of the rebuttal mentions the US constitution.

Despite the ban of segregation in 1968, racial/ethnic fluidity has been limited over the past few decades, leading to further geographic and socioeconomic discrepancies in access to health care and education. Although the constitution is mentioned in the article, many of the delegates at the original Constitutional Convention were slave owners; and although the historical perspective has been presented, it has been lacking in a critical analysis of the interwoven fabric of racial barriers to medical care and education. Morality is not a sine qua non with legality, and our obligations for inclusivity should be based on providing optimal care for a diverse patient base rather than perfunctory fulfillment of diversity mandates.

The phrasing is a little confusing, but if I am understanding what they’re trying to say, the rebuttal claim that racial/ethnic fluidity in Medicine has been static since 1968 willfully ignores the explosion of brown faces in Medicine since 1965. Dr. Wang is ethnically Chinese, I’m an immigrant from India, and the cardiologist authors of the rebuttal are below:

It would appear to most casual observers that while there are many that are unhappy with the racial makeup of physicians today, the field looks a lot different than it it did in the 1960s, with Wang and the authors of the rebuttal being living proof of that change.

But the most startling assertion in the rebuttal relate to the United States Constitution. Apparently Wang’s concerns about the constitutional propriety of current day practices in the field of medicine are to be dismissed because "the delegates at the original constitutional convention were slave owners”. This should come as a surprise to constitutional lawyers who usually have to make arguments compatible with some interpretation of the constitution of the United States. Generally, arguments that advocate ignoring the constitution don’t pass muster, but perhaps the day cardiac electrophysiologists opine in front of the Supreme Court justices fast approaches.

To summarize the whole affair briefly— a cardiologist published a peer-reviewed paper that made the argument affirmative action policies in medicine may not be working out as intended, and could be violating the law. In response, the cardiologist was demoted, his paper retracted, and a viral social media campaign labeled him a racist.

The wider medical / cardiology community either joined in the pile-on, or were silent.

In the words of Cardiologist, Purvi Parwani discussing the treatment of Dr. Wang:

So, about those good guys.

They did win, right?

Anish Koka is a cardiologist. Follow him on twitter @anish_koka

Dr. Wang is suing his employer, as well as Chief of Cardiology Samir Saba, Cardiology Fellowship Program Director Katie Berlacher, and others for retaliation of his expression of views that the cardiology field in general and the Pitt School of Medicine/UMPC were engaging in illegal discrimination on the basis of race and national origin.

“Identity politics” are evil. Jesus taught the opposite of identity politics. Thankfully, he already won. Happy Easter a day late!

The ‘race’ to the bottom is running apace!