Outpatient vascular care : Good, bad or ugly?

Filling in the holes of recent stories in the New York Times, and Propublica on the outpatient care of patients with peripheral arterial disease

Most have gotten used to egregiously bad coverage of current events that fills the pages of today’s New York Times, but even by their now very low standards a recent telling of a story about peripheral artery disease was very bad.

The scintillating allegation by Katie Thomas, Jessica Silver-Greenberg and Robert Gebeloff is that “medical device makers are bankrolling doctors to perform artery clearing procedures that can lead to amputations”.

The reporters go on to tell a story about patient Kelly Hanna, who presented to a physician, Dr. Jihad Mustapha, in a private clinic with a festering wound. After being diagnosed with a poor flow to her leg that was likely contributing to the wound, Dr. Mustapha performed multiple procedures on her leg to improve blood flow in an attempt to ward off a future amputation. The procedures were unsuccessful, and Ms. Hanna ultimately did need an amputation.

The Times also briefly touches on some other patients of Mustapha who had bad outcomes. The majority of these cases appear to be related to complications patients suffered during surgeries. Multiple surgeons reported having to have done multiple procedures on Mustapha’s patients who had had complications. In 2020, the state medical board investigated Dr. Mustapha and referred him to the Michigan attorney general. An expert hired by the state medical board reviewed 8 cases and concluded the practice was characterized by overtreatment and poor documentation. Mustapha reached a settlement with the Attorney general where he was fined $25,000 but did not acknowledge any wrongdoing.

Mustapha questioned the expertise of the medical board that was overseeing him, and noted that any significant wrongdoing would have resulted in a much more significant punishment.

I’m sympathetic to Dr. Mustapha after reading the New York times article for a number of reasons. The claims of wrongdoing appear to stem from:

Dr .Mustapha is a high volume operator that does lots of limb salvage procedures and has been paid a lot of money for this.

Vascular surgeons at nearby hospitals had complained because they were seeing “a lot” of his patients having complications.

An insurance company reported 45 patients over a course of 4 years needed amputations.

Device companies that manufacture the tools used by physicians to open up arteries provide loans to physicians to buy these tools.

There have been many more attempts to open arteries that have taken place in private clinics since reimbursement rules changed.

This is all extraordinarily thin evidence to suggest wrongdoing on a grand scale.

First of all, the case the New York times chose to present involved a patient with a wound due to poor peripheral blood flow from critical narrowing of arteries. Presenting with a wound like this is a very poor prognostic sign, and indicative of Chronic Limb-threatening ischemic (CLTI) : a condition that carries a 1 year amputation rate of 20%, meaning 1 in 5 patients presenting like Ms. Hanna end up with an amputation. Dr. Mustapha, who also happens to be widely regarded as a pioneer in the PAD field, self reported a 30 day amputation rate of 1.3%. This provides the appropriate context for the 45 amputations in 4 years reported by an insurance company. A successful, high volume operator working with difficult cases is bound to have numerically more complications. Without denominators, “more complications” means little.

It is possible that Dr. Mustapha’s rate of complications look good because the patients being taken to the lab are lower risk patients who shouldn’t be in the lab having procedures done. However, there is little evidence presented to suggest that this is the case outside of anecdotes from disgruntled former partners who note they were pressured to refer patients for vascular procedures.

It is similarly challenging to know what to make of the complaints from neighboring vascular surgeons about complications in Dr. Mustapha’s patients. The surgeons are generally unhappy with other specialties managing PAD patients without their involvement, and they also don’t know the the denominator to know if the complications occurring are at a higher rate than what would be expected.

Unfortunately, and especially in complex patients, wires may break while doing procedures, and the only treatment at that point is a vascular surgeon. Again, without knowing the denominator of total cases, it’s irresponsible to suggest there is something deeply wrong going on.

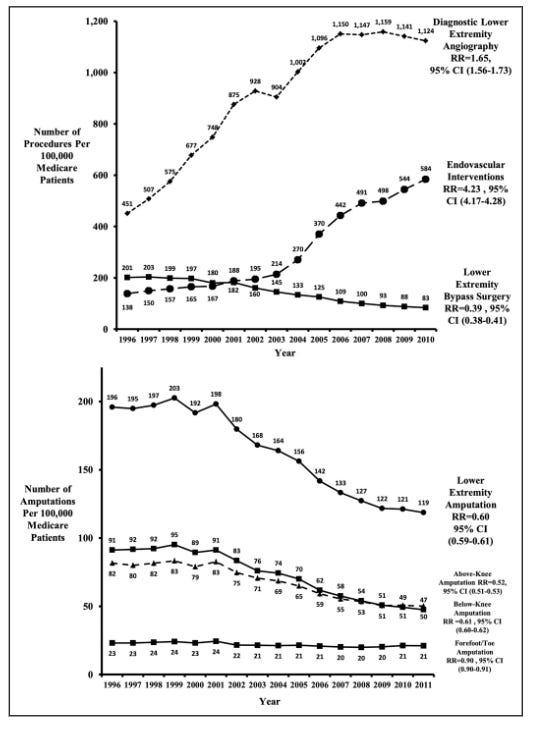

The New York Times also accepts as fact the assertion from surgeons that more endovascular procedures lead to more amputations. While this may be true in individual cases of unscrupulous physicians, the national story does not support this claim. Despite the significant increase in the complexity and illness of patients that have been presenting with peripheral arterial disease, the rate of amputations has actually gone down, despite the fact endovascular interventions have rapidly increased.

While it’s possible to attribute the lower amputation rate to other improvements in wound care, the likelihood of this being the fundamental driver of fewer amputations over time is very low. At the very least, the graphs make it highly unlikely that the main contention of the New York Times article - that higher rates of endovascular interventions leads to more amputations - is true.

It’s unfortunate the New York Times screwed this story up so much, because there are real issues to consider in this space. There is little question that the financial incentives to find and treat peripheral arterial disease leads to inscrupulous operators that harm patients. Propublica does a much better job in their deep-dive into the PAD story which focuses on vascular surgeon Jeffery Dormu.

Jeffery Dormu was a double board certified vascular surgeon who was paid $13 million dollars by Medicare alone between 2013 and 2017. In 2018, he even opened a state of the art lab nicknamed “the Watcher” and was paid $18 million from Medicare in the next 3 years.

These payments made him one of the highest paid vascular surgeons in the country. The numbers reflected a high volume of care delivered but there were concerning indications much of the care delivered was unnecessary. Unlike the New York Times story that featured a patient with a non-healing wound that put her at high risk of losing her limbs, some of the patients featured in the Propublica article had mild symptoms. Propublica does a pretty good job diving into each patient story, but the US medical malpractice system is challenging for laypersons. Highly paid expert witnesses on both sides make strong assertions, and lawsuits are frequently settled because it makes the most financial sense to do so, not because the case itself may merit it. So its worth a closer look at the patients discussed

The first patient Propublica discusses is Mr. Rosenberg, an auto mechanic who sought out care from Dormu for increasing leg pain.

12.27.2016. Mr. Rosenberg meets Dr. Dormu.

A lower extremity arterial ultrasound revealed elevated velocities in the right proximal superficial femoral artery.

1.19.2017. Dr. Dormu performed an aortogram of the bilateral lower extremity with bilateral iliac runoff, which revealed a 90% stenosis of the right superficial femoral artery and 100% occlusion of all three tibial vessels. Based on these results, Dormu performed a percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty and a mechanical atherectomy and stenting of the right superficial femoral artery and stenting of the right superficial femoral artery. Dr. Dormu also performed a mechanical atherectomy of all three tibial vessels.

3.23.2017. In response to increasing severity of his leg pain, Dr. Dormu performed another angiogram. These studies revealed an 80% stenosis of the left superficial femoral artery and 100% occlusion of all three tibial vessels. Dr. Dormu performed a percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty, a mechanical atherectomy, a stenting of the left superficial femoral artery, a mechanical atherectomy of all three tibial vessels.

3.31.2017. Mr. Rosenberg presents to the hospital complaining of left foot numbness and coolness when laying down. He is again sent to Dr. Dormu, who on the same day, performs another angiogram which revealed an in-stent restenosis of the superficial femoral artery stent and a 60% stenosis of the tibioperoneal trunk. Dormu replaced the stent due to “recoil”, and performed another mechanical atherectomy and a percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty of the left superficial femoral artery and a percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty of the tibioperoneal trunk.

4.1.2017. Mr. Rosenberg again presents with leg pain. Dr. Dormu performed another angiogram which revealed an in-stent occlusion/restenosis of the superficial femoral artery stent and restenosis of the tibioperoneal trunk. Based on the results, Dormu performed a percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty of the left superficial femoral artery and tibioperoneal trunk. Another superficial femoral artery stent was placed as well. Dormu also sends Rosenberg to the hospital after this procedure for evaluation for bypass as well as a thrombolytic.

4.2.2017. A thrombolysis is performed in the hospital via a catheter.

4.3.2017. Rosenberg develops a large hematoma and a cold foot. Dormu removes the catheter and recommends an amputation.

4.8.2017. Rosenberg is transferred to another hospital for a second opinion. A CT angiogram shows a left common femoral dissection. No blood flow is seen below the mid thigh. All stents were occluded. On the same day, Mr. Rosenberg undergoes an above the knee amputation.

Dr. Dormu’s expert witness, Dr. Garry Ruben, said the interventions were warranted, and blamed Rosenberg’s course to not consistently taking anti-platelet medication that may have kept the stents open, and his preexisting medical conditions.

Mr. Rosenberg’s expert witness, Dr. Christopher Abularrage, a vascular surgeon at Johns Hopkins, disagreed. He found several “breaches of the standard of care.” : failing to prescribe conservative therapy and lifestyle modifications first, and persisting with “unindicated, endovascular interventions in the face of persistently poor outcomes and diminishing returns”.

It’s possible that Mr. Rosenberg did have severe claudication causing him to have pain at rest, and that he was appropriately diagnosed. There is little question, however, that there appeared to be no attempt to attempt to conservatively manage Mr. Rosenberg’s symptoms. Only 23 days passed between the initial meeting with Dormu, and the subsequent intervention on his leg.

The Maryland State Medical Board initiated an investigation in 2020 after a patient complaint that noted Dr. Dormu recommended an angiogram for severe itching in the legs. A second opinion from another physician at another facility resulted in a normal ultrasound. The itching turned out to have been a bad reaction to an insect bite. This and other patient complaints triggered a review of 11 patient records by two independent peer reviewers who found that not only were conservative measures not employed prior to progressing to more invasive procedures, but patients with normal diagnostic studies were also subject to invasive procedures with “no clinical justification”.

The cases supported the claim that Dormu was performing procedures with serious complications in patients that did not need them. Patient 6 could walk a mile prior to having symptoms. After a procedure with Dr. Dormu, the patient endured worsening symptoms and an inability to walk after the initial left leg arteriogram performed by Dormu. Dormu then continued to perform left leg arteriograms on Patient 6 despite worsening perfusion and more severe symptoms in that leg.

Dormu also appeared to misdiagnose individuals, incorrectly diagnosing Patient 10 with peripheral arterial disease, and then performing procedures that ultimately worsened lower extremity perfusion. In October 2022, the state medical board found him in violation of state medical law, citing, in part, his overuse of procedure. He was fined $10,000, his license was suspended and he was placed on a two-year probation, during which he must be supervised.

It does not appear Dormu has practiced since.

The story for Dr. Dormu gets even stranger. A press release from May 24, 2023 advertises a TV show medical drama that purports to be a retelling of the life of Dr. Dormu that references a past as a drug kingpin in Washington DC.

This hard-hitting retelling of Dr. Jeffery Dormu’s dangerous past as a former District of Columbia drug kingpin intersperses storylines from the doctor’s past and present. The series navigates his life and illustrates how one margin of error could mean the difference between life or death on the streets as well as in the operating room. From narrowly escaping life as a Liberian child soldier, organizing one of the largest gangs in DC history, the Gangsta Chronicles and becoming a drug kingpin, to attending an ivy league school, Dormu went on to win a civil rights lawsuit against four corrupt police officers. During the span of his career, he has surgically saved tens of thousands of lives and built the only black owned cardiovascular hospital in the world, a multi-million dollar facility. Margin of Error is a unique rags to riches story that will take fans on a multi-sensory journey.

The contrast between the New York Times story and the ProPublica story is striking. The New York Times chose to attack a well-respected pioneer of the field who does a lot of procedures that result in some patients having complications and needing amputations. The grievances about practicing below the standard of care come almost entirely from neighboring vascular surgeons with an axe to grind. A review from the State medical board and the Attorney general resulted in a fine with no admission of wrongdoing. His license was not suspended, and he continues to operate a busy practice today.

ProPublica showcased a vascular surgeon with a checkered past who clearly was unable to diagnose peripheral arterial disease appropriately and was doing a high volume of procedures on asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients. The investigation by the state medical board resulted in a suspension of his license, he does not appear to be actively practicing today, and the website for his vascular center is no longer available.

Both articles unfortunately leave readers with the impression that all endovascular interventions are suspect and are primarily driven by a need for profit rather than any desire to help patients.

Academic vascular surgeons who have been long banging the drum of overuse of endovascular procedures seized on these articles to call for greater regulation of vascular centers and the operators working at these facilities. Dr. Joseph Mills , President of the Society of Vascular Surgery encouraged vascular surgeons be involved in the decision making process for patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD), and noted that very few patients with PAD actually should qualify for interventions.

But everyone involved with taking care of patients with PAD agree that critical peripheral arterial disease leading to amputation is a major problem that disproportionately impacts poor, black communities. Even the vascular surgery comment on the New York Times article ends with an entreaty to the media :

SVS urges media professionals to be diligent in presenting health care and medical information that is fully balanced, as coverage could lead to patient distrust and delays in necessary care with potentially adverse consequences.

Unfortunately, the pull for the salacious story line that sells regarding greedy doctors hurting patients in the name of the dollar is too strong for most in the media to resist. In choosing the easy path to clicks, ignored are the real issues :

Medical training programs (funded with taxpayer dollars) that appear to rubber stamp the unethical and the incompetent. The egregious practice patterns of Dr. Dormu should raise serious questions of the programs that trained him (Vascular surgery specialization at Deborah Heart and Lung). Should programs and program directors responsible for signing off on trainees as competent to perform procedures independently face sanction when graduates of their program fail to do so?

If training programs are turning out some combination of incompetent and unethical graduates, the onus falls on state medical boards responsible for protecting the public from bad operators. The system appears to work in the case of Drs. Dormu and Mustapha, but the timeline for corrective action is too long. The first complaint reported to the Maryland medical board was in October of 2020. The resulting investigation and sanction to suspend his medical license did not take place until late in 2022. Two years of a dangerous operator like Dormu practicing medicine is too long.

The peer review process as a means of regulation appears to be highly susceptible to internecine squabbles that make it difficult to delineate right from wrong. Vascular surgery has a strong stance that has a protectionist bent to it. It is clearly in their interest to cast other specialties operating in this space in a poor light. Academics, especially, are hostile to all work being done outsie their purview. The currency in health systems is volume of procdures performed. Private clinics located in areas with a high prevalence of PAD threatens hospital volume. This makes peer review provided by vascular surgeons as a means of regulation suspect.

Atherectomy is controversial in part because the evidence in the form of clinical trials for their use is poor. More trials may shed light on exactly how inappropriate atherectomy is and define the population best suited for it.

Reducing or changing reimbursement for procedures in the outpatient/non-hospital setting is a common solution proffered by a number of commenters. Unfortunately, many of these commenters are in the academic hospital space and have much to gain from this type of regulation, and ignores the possibility that there have indeed been countless limbs saved by expanding access to those most at risk to revascularization.

This is certainly a good discussion worth having that deserves attention. The New York Times doesn’t appear to be the best place to moderate that debate.

Anish Koka is a cardiologist. Follow him on twitter @anish_koka

To listen to more of the discussion, tune in at 1 pm EST July 23rd on TwitterSpaces (Go to twitter and click on the pinned tweet on my profile @anish_koka )

These outpatient procedure “Surgery Center” clinics allow the physician to collect both the procedure and hospital fees. The hospital fees are MUCH larger, e.g. a rough estimate for gallbladder removal is a procedure fee of $1,000 and a hospital fee of $20,000.

The public for the most part is unaware of the difference between having a major operation done in a private Surgery Center where the temptation for the operator is about 20 fold increase in reimbursement.

But the most frightening aspect of these “Surgery Centers” is that they are grossly under equipped to handle complications and critically ill patients. THEY ARE NOT A HOSPITAL and should not receive the same hospital fee because they do not provide the same service.

As a physician on the receiving end of these complications (a tertiary academic medical center) this is not an issue of competition. It’s an issue of patient safety.

Given the difficulty in obtaining revascularization of stenotic arteries under the most favorable of circumstances, increasing the supply side of the medical economics equation with outpatient centers is understandable.

It seems to me that the problem would be with carefully evaluating risk factors that should properly result in referral to a hospital-based vascular surgeon. To allegations of "overtreatment," I remain highly skeptical. Yes, it occurs with dreary regularity in some quarters, but what no one seems willing to discuss, is the influence of "stealth rationing" on the potential overuse of "conservative" treatment modalities that result from demand far exceeding supply.

One of the examples used above was that of an auto mechanic. If he was treated and released to resume his occupation, the very same conditions contributing to his stenosis were also resumed. Mechanics stand in one place for the majority of their workday, older mechanics are usually exhausted by shift's end and the daily shop-floor-to-couch routine continues. Time and time again, we see patients such as chefs and mechanics return to work as soon as they're physically able to stand again. Without lifestyle and occupational changes, their prognosis is less than stellar.

This opens an entirely new discussion; the consequences of recommending long-term disability payments for those whose sole occupational skill is killing them. This discussion requires its own set of interviews and articles. Given what I have observed over the last four decades, I suspect that finding practitioners willing to speak frankly and openly may be rather challenging.